Documenting multi-repository projects

Contents

This blog post is a de-powerpointized version of a brownbag session in Pivotree. The goal was to increase awareness of tools and techniques for information / knowledge capture in the projects, specifically focusing on producing quality documentation so that everybody in project can access it and contribute to it, not only developers. We wanted to look at the tools that would allow engineers keep using their tools of trade (without impact on developer’s productivity) and at the same time make the information available without duplication of work to increase re-findability of information.

We are introducing standards, tools and best practices for documentation and suggesting workflow that can simplify and streamline the process of creating a documentation and keeping it up to date.

Note: it was also published at our workgroup blog.

Why documentation is important

In commercial environment, quality (and often existence) of documentation is important factor in determining what will be the cost of maintaining the codebase.

Whether or not the documentation is available / complete / up-to-date can greatly impact:

- whether the code will be correctly used

- how fast it will be available for reuse / modification

- how efficient / dynamic will onboarding / transfer of people within the team work

In OpenSource world quality and comprehensiveness of documentation is a matter of project survival. With all other things (code quality, functionality, community size etc) comparable or equal, the project that makes it easier to understand the code, has more examples and helps make the learning curve less steep, will have better adoption rate and much greater chance to attract the contributors and users. In the end, this will decide whether the project will live and prosper or gets abandoned.

There is another aspect. While documenting a system: we give it another look and create an “internal checkpoint” that helps to answer questions like:

- Is it really complete ?

- What is missing ?

- Are edge cases covered ?

- Does it do what it should do ?

This can have a great impact on the development of a project and should be an ongoing process, not left for “afterwards” when the coding is done.

Writing documentation is explaining the code to unknown audience. One can consider it an instance of a “Rubber Duck debugging” session without any particular problem on the table. It is very useful exercises and quite often it makes visible overlooked scenarios and generally improves quality of code by the simple process of giving it another look from a different angle, wearing a different hat than coders do.

What makes a documentation good and/or useful

The criteria for good documentation we aim for is a documentation that:

- is up-to date

- is accessible to the proper audience (all project stakeholders)

- is it easy to extend / modify

- has its lifecycle defined and tied to project lifecycle

- is it easy to find: has high degree of re-findability

Code vs Documentation: what we document

Documentation contains parts with different degrees of closeness to a project code.

At the closest end, there is documentation that lives inside the source code files. This type of documentation is focusing on details such as explaining purpose and functionality of functions, parameters, explanation of the details. It is crucial in the “forensic” / maintenance situation - debugging the code and searching for an answer to the question “why does this not work” ?

While this type of documentation is extremely useful and important, we cannot limit our focus at this level. The problem here is that at this level of detail the documentation is rather hard to read: it is not clear where to start, where to go next - it does not tell a story and it’s structure is dictated by physical code structure.

This is where additional, higher level description comes into play: system description, explanation how does the subsystem / whole system work, what is a module architecture, what are interfaces between modules, subsystems.

This type of documentation covers information outside of scope of a single source file, but is still source code related. It includes examples of APIs, examples of proper use of the code. It should represent a logical view, that is different from the code structure.

At the highest level of abstraction from the code we have documentation of architecture and project design, user documentation, installation and project lifecycle documentation.

All this type of documentation needs to be represented / written in some form and exist is some place. Quite often, the different levels of documentation can be found in different places using different tools. I am trying to show why this is not the best approach and present tools and workflows that allow documentation and code coexit in the same place.

Where does your documentation live

There are two places where documentation can live:

- in the same source code repository as the code

- somewhere else

There are several advantages of using the same repository as the source code:

First, it is the audience - big part of the documentation is written by (current) developers for (future) developers. This way it can be managed together, using code version friendly tools. In order to do that, we need to use code version friendly formats - text based formats.

Second - using the same repository synchronizes release cycles of the documentation. It is much easier to update the CHANGELOG.md when it is right there and to make it part of the next commit than to remember to go to some Wiki and do it there. How many similar lines as the following one have you seen during your career ?

... SOME CODE

# TODO: Update the Release Notes in the Wiki - URL

... more code

Which gets us to second location for the documentation: somewhere else - meaning “separate from the code”.

Elsewhere can include places like “in a Wiki” - which is not great to really unhappy places such as Word documents on a file share.

There are many issues with this approach: by going elsewhere for the documentation, we need to use separate credentials, loose the direct link to code. Some part of documentation (source code comments) still stays with the source, but other parts - the higher level - are now elsewhere. The “one source of truth” is lost and often documentation in Wiki contains different information than the actual code.

With “elsewhere” we get inherently different release cycles for project code and documentation: updating the documentation is decoupled from code changes and project releases which impacts the “up-to-dateness” of the information. It also makes the automation and CI/CD much more complicated.

We also get different search scopes: to find something, two searches are necessary - one over the source code and one over the documentation place.

As the information related to code lives in two places, we will not have a single source of truth: if there is an overlap and the one place does not agree with the other, there is a risk of using the wrong one. Transfer of information between two locations leads to unnecessary work.

Note: with all the issues mentioned above, Wiki at least has a built-in mechanism of versioning and diff capability with change tracking and prevention of information loss / overwriting. A much worse situation is using separate word documents on file share - the binary format makes content comparison more complicated and file share is susceptible to overwrite / information loss. Where Wiki falls short is that it is “single threaded” - there is a single sequence of changes (albeit made by different contributors). In the code world, the typical situation is that we have multiple active branches representing (at minimum) current - deployed application, bug-fix branch (small changes with short release cycle) and future

With all that said, we can ask what is the main motivation of using the Wiki as a separate documentation store ? It is usually easy to edit (web interface with some form of WYSIWYG) and formatting capabilities of the Wiki compared to plain text inside the source code repository (headers, bullet points, tables, embedded pictures, links etc). An idea of accessing text based file in a Git repository and the developer’s prefered tool chain (that is command line oriented and quite technical) may seem at a first glance to be to complicated for non-developer members of the team: project managers, business analysts, product managers / stake owners.

In the next part we will show that if a proper format for a documentation file is selected, we can address both of these concerns without leaving the realm of the single source code repository. Let’s have a look at available documentation formats from a maintainability point of view and see how these can impact the user experience for content contributors.

Formats - from maintainability POV

What makes document format “good” from maintainability perspective is that it must be simple and text based.

Similar to source code files.

This allows easy diff creation and versioning and most importantly, easy merging when different versions of code (and documentation) are being worked on in parallel.

Unfortunately, pure text is not visually appealing and lacks lots of features such as a standard way to embed images and structure parts of text (such as heading). There is a text based format that has all these features and more but it is very impractical for manual editing - the HTML.

The middle ground between plain text and full presentation capable HTML is markup - a standard of formatting plain text file so that it can be easily transformed into HTML representation. Even better, all major source control platforms - Github, Bitbucket and Gitlab - support rendering the markdown files as nicely formatted HTML with headers, links, tables and embedded pictures while allowing editing the source form of the file in the browser. The word “markup” indicates how it works: there are special, designated characters or words that indicates the formatting or structure of a piece of text - e.g. indicating header, table or embedded image - it marks it up for presentation.

The result is good looking, easy to version and easy to edit documentation files.

Considerably worse choice from maintainability point of view are binary proprietary formats - e.g. most famous one would be Word. They are either binary (doc), but even if not, the internal XML based format is not suitable for neither comparing nor editing without proprietary tools. Using the open source alternatives does not help - they pose the same problem and the fact that one does not have a commercial license to use them does not help either.

Absolutely worst format from maintainability point of view are systems storing the documentation in a database, which essentially turns a document into a proprietary blob and then hides it inside a much bigger proprietary blog, accessible only through a dedicated proprietary interface.

So the best bet is selecting a markup format that is simple enough to be easy to learn for non-technical users, expressive enough to produce great looking rendered documentation and with tool support allowing in-place editing on Github/Bitbucket, tools for advanced user as well as support for automation of documentation rendering. The rendering does not necessarily need to be only HTML - many markup toolchains can produce PDF or ebook format such as ePub. These will be the criteria we will use to select best markup format for our use case

Markup formats parade

At the end of 2020, we can safely say that the big 3 worth looking at are:

- Markdown

- AsciiDoc

- RestructuredText

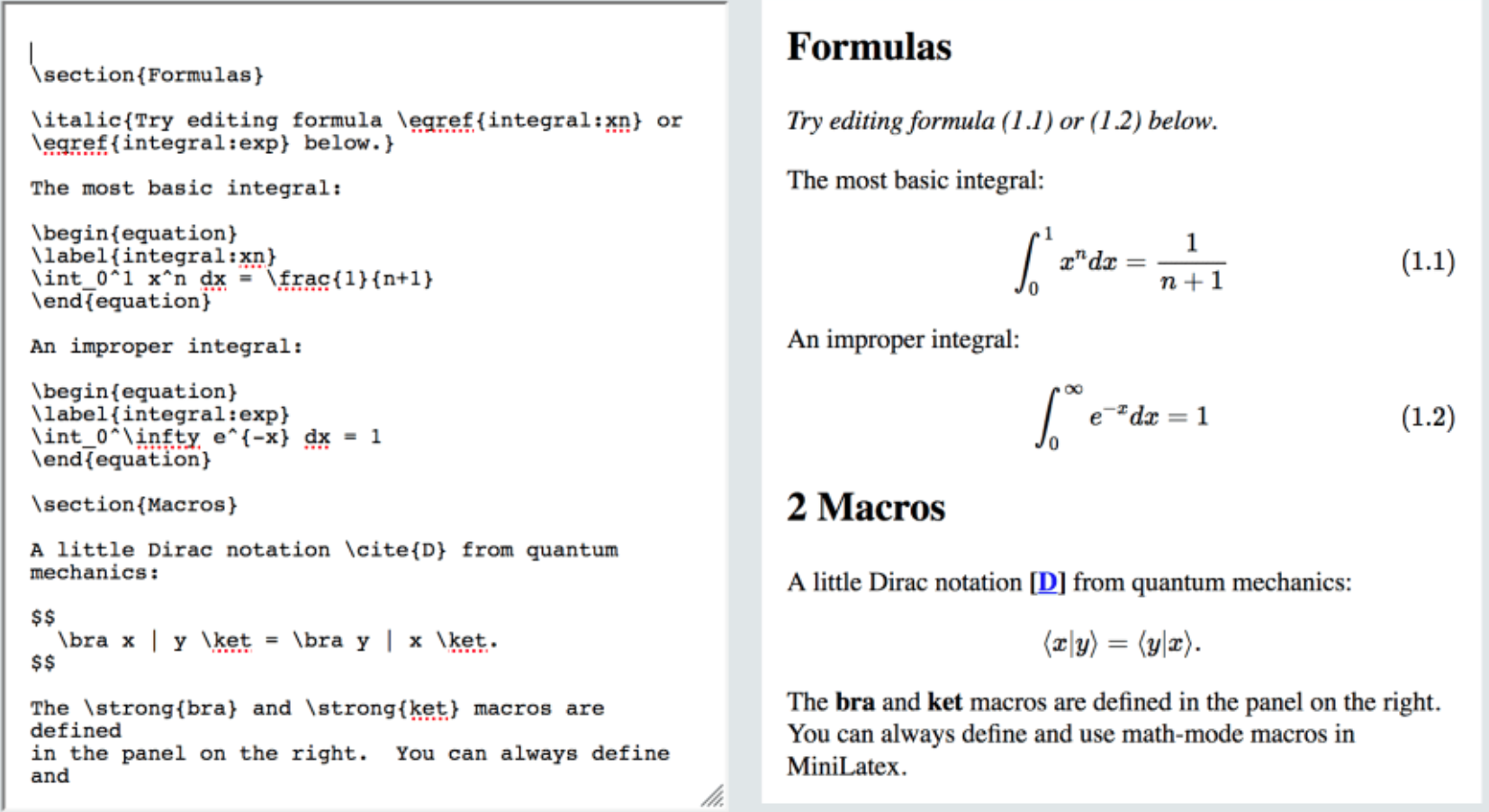

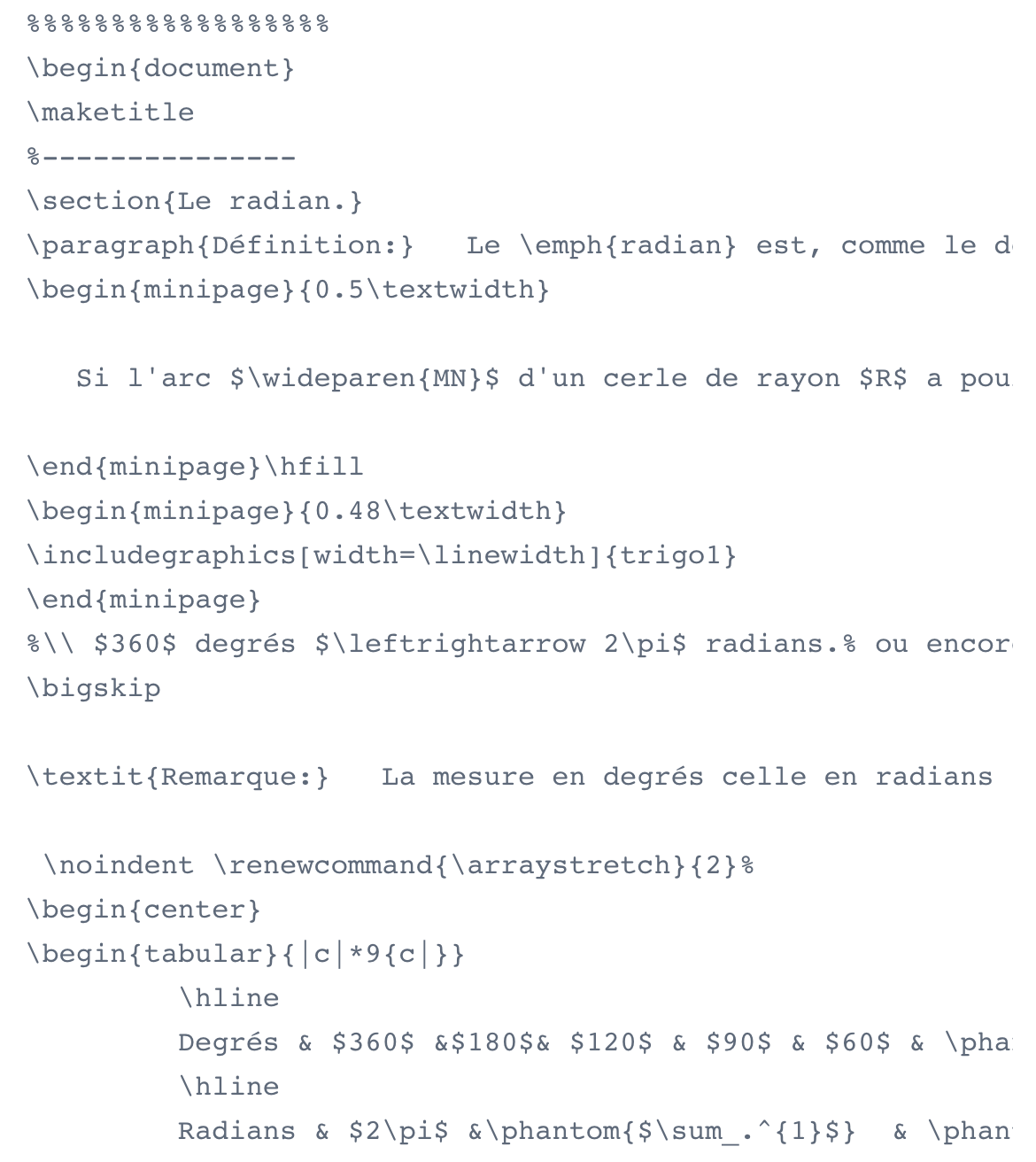

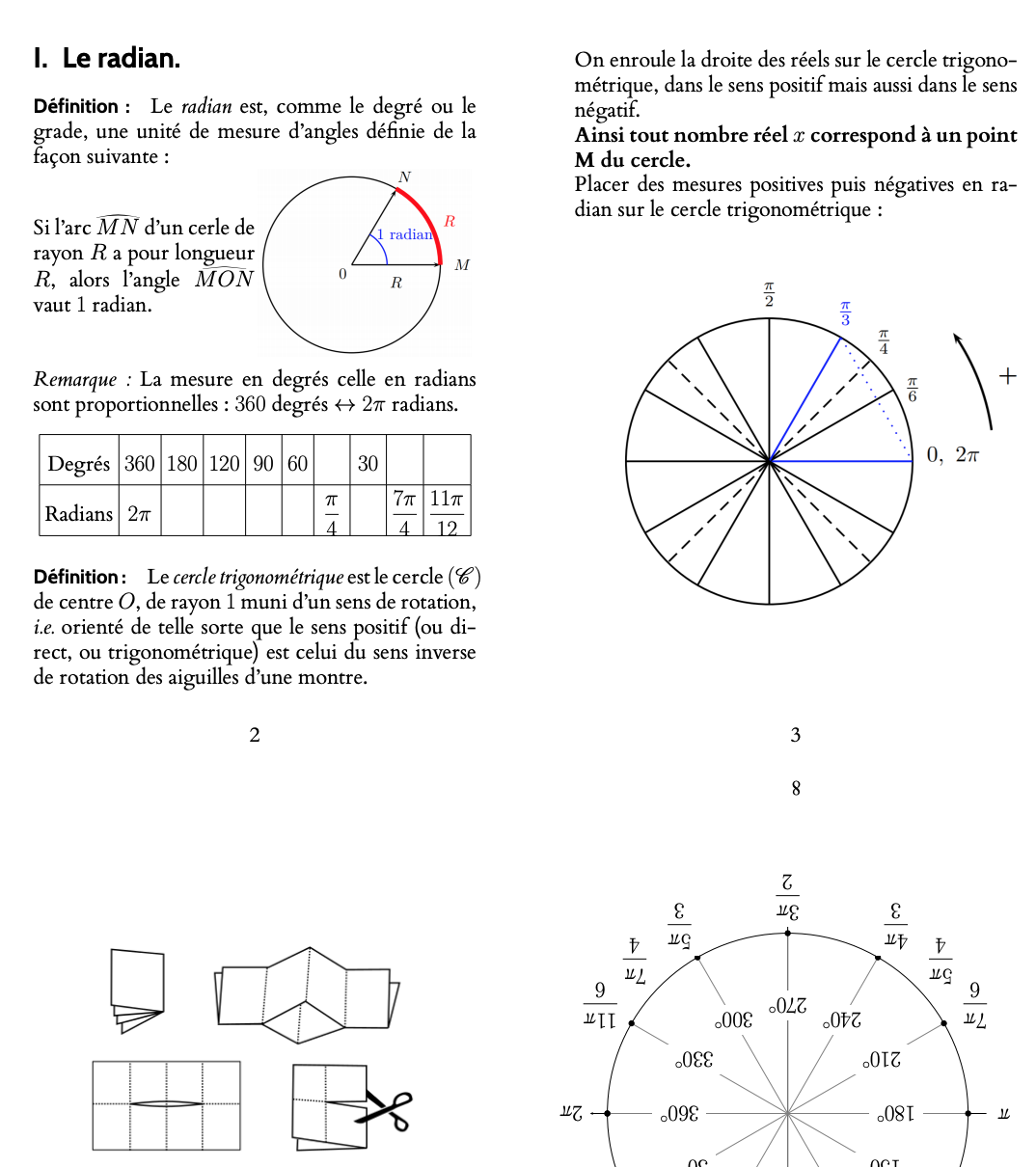

with LaTex as honorable mention.

We were quite considering it seriously because even if technically it is a markup, but it’s capabilities and complexity is in a different league. It shines for creating scientific articles with complex mathematical formulas and beautiful exact typography and the whole toolchain is targeting a very different audience and use cases.

Here are few examples that can be a small peek into how powerful (and complex) LaTex markup is:

Side-by-side source/rendered:

A snippet of the source

.. that renders this result

Markdown

Markdown is by far the most popular markup format in use. It is also the simplest / easiest to use from the big 3. It has widest tooling support - most IDEs and major editors support preview mode (e.g. Visual Studio Code, PyCharm, Atom) - either OOTB or via plugins. Not surprisingly, there are lots of generators that take one or more markdown files and produce good looking web pages or web sites. It is well supported by CI/CD pipelines and most use cases is focused on producing HTML output

Among disadvantages of Markdown is lack of standardization - there are dialects and supported features in different toolchains may differ. One of the dialects seems to be approaching ‘standard’ status - GFM also known as Github Flavored Markdown, which together with ‘Material theme’ enjoys great popularity among users. The second disadvantage is being less expressive / less powerful than the others - a consequence of being simpler

Few pointers

- https://markdown-it.github.io/

- https://www.markdownguide.org/cheat-sheet/

- https://guides.github.com/features/mastering-markdown/

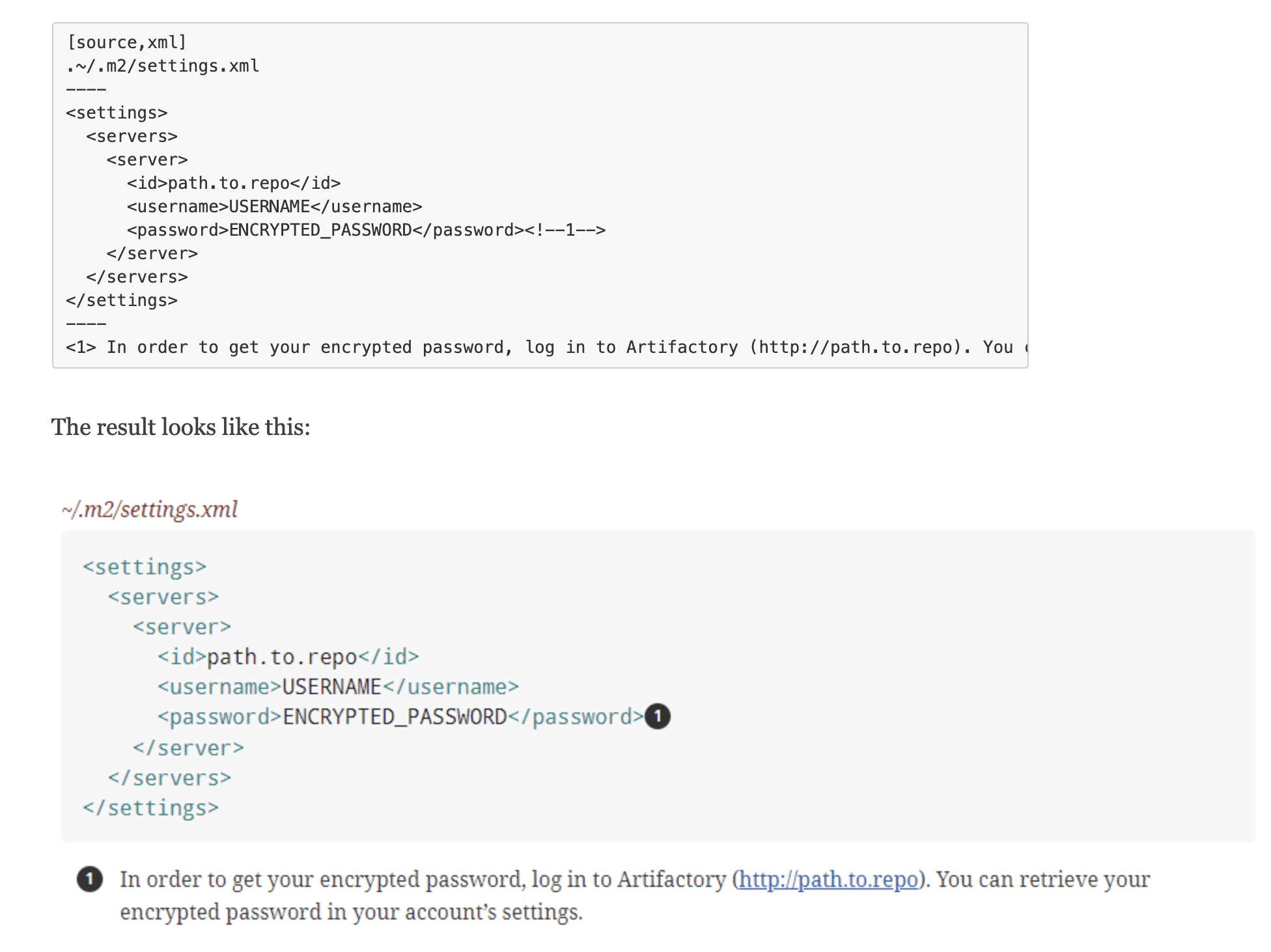

AsciiDoc

AsciiDoc (https://asciidoc.org/) is format used by toolchains that many book authors use to author and produce eBooks and printed - OReilly among the most notable ones see (documentation on Atlas)[https://docs.atlas.oreilly.com/writing_in_asciidoc.html]. AsciiDoc has many features well suited for larger projects - e.g. support for glossaries, which is no surprise as it started as a markup lightweight alternative to DocBook - XML based format for book authoring.

The best known tool for AsciiDoc is AsciiDoctor - check its functionality and some more details on differences between AsciiDoc and Markdown here, and here. The second link shows few of the “killer features” of AsciiDoc for code documentation

- e.g. annotation of the code snippet rendered as numbered callouts:

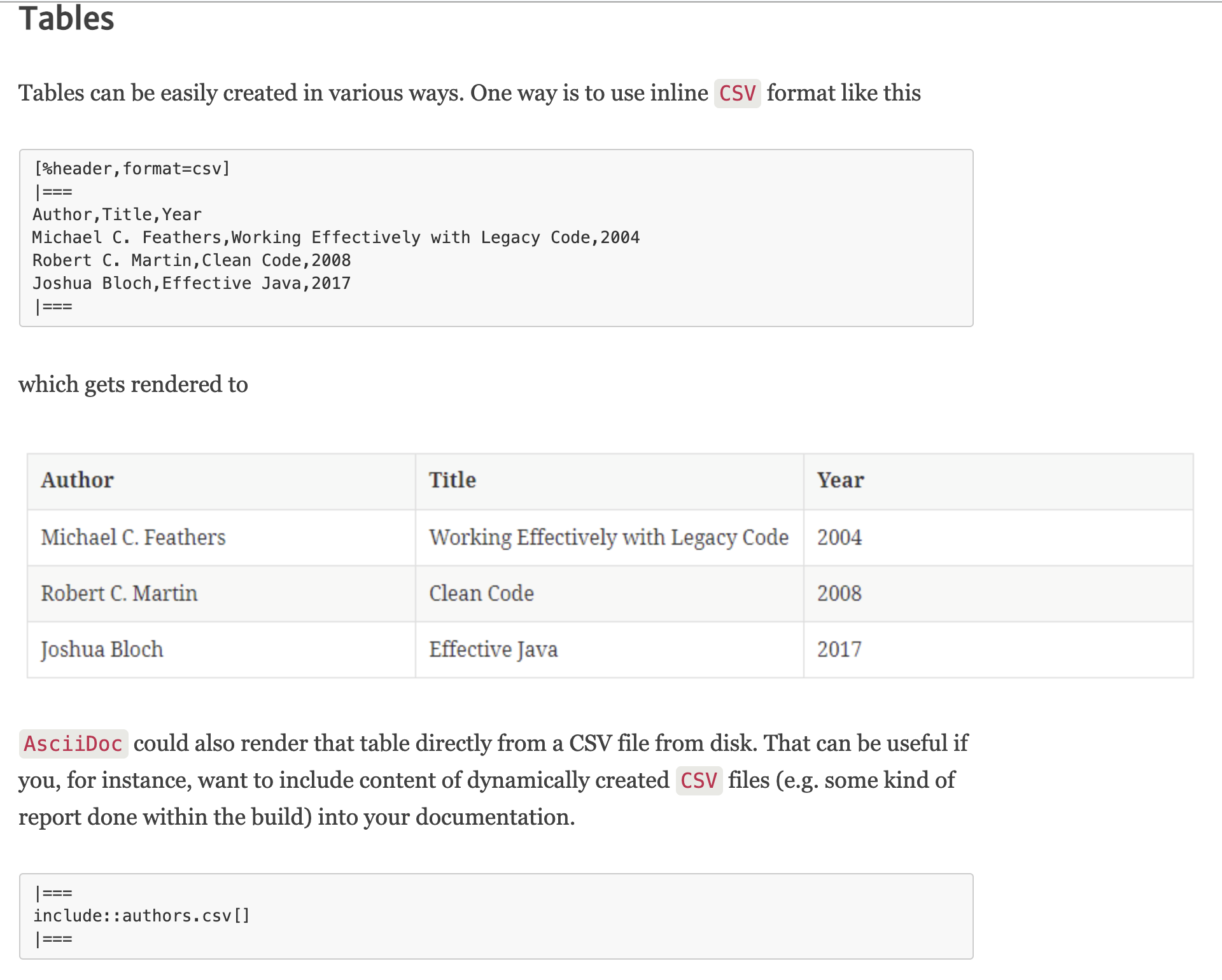

or treatment of the tables:

RestructuredText

The last of the big three is coming from and is focused on Python and programming languages documentation. It has excellent capabilities to combine documentation extracted from source files - (in Python world “docstrings”) with the text only files into a coherent, larger body of information. It was originally created as the format for Docutils documents and it’s initial release dates back to 2002 - so it is older than Markdown.

It’s superpowers are in the area of inweaving the code and the text, with extracts from the source files. It is very easy to include partial content of the source code directly into the text, create a table of content or well defined extensibility. It’s “native” toolchain is called Sphinx and it’s showcase is ReadTheDocs - documentation hosting site based on Sphinx but also supports Markdown. Another good example of RestructuredText capabilities is anaconda documentation or sphinx documentation

Restructured text is more complex and unfortunately more fragile than the previous two formats. It is quite easy to write invalid markup and I have personally run several times into weird formatting issues (unlike with Markdown or AsciiDoc). After using it for over 1 years for personal projects I gave up and switched to Markdown - and I was not alone that ended up doing so.

It is also least popular and mostly unknown outside of the Python community.

Here is side by side comparison of the syntax similarities and differences between these formats.

… and the winner is:

Markdown. The ease of use, simplicity, wide toolchain support and being the “native” markup for all three Git hosting sites (which we all use for different sides of the business).

As for toolchain, we have selected two options: MkDocs with Material Theme and Gatsby.

Authoring - as easy as Wiki

The way you write the documentation using Markdown, depends on what kind of role you play in the projects. For developers, the great news is that you keep using whatever tools you are happy with: any major editor (Visual Studio Code, Atom, Sublime Text, vim, emacs, Notepad++ - etc) supoort Markdown, in many cases including the preview functionality - either directly of through plugins. The documentation is simply a set of files living under the ./docs folder in your repository.

If you are not a developer and do not really know all the details regarding git, cloning, branches and pull requests, no worries: there is a Wiki-like way to contribute and document everything.

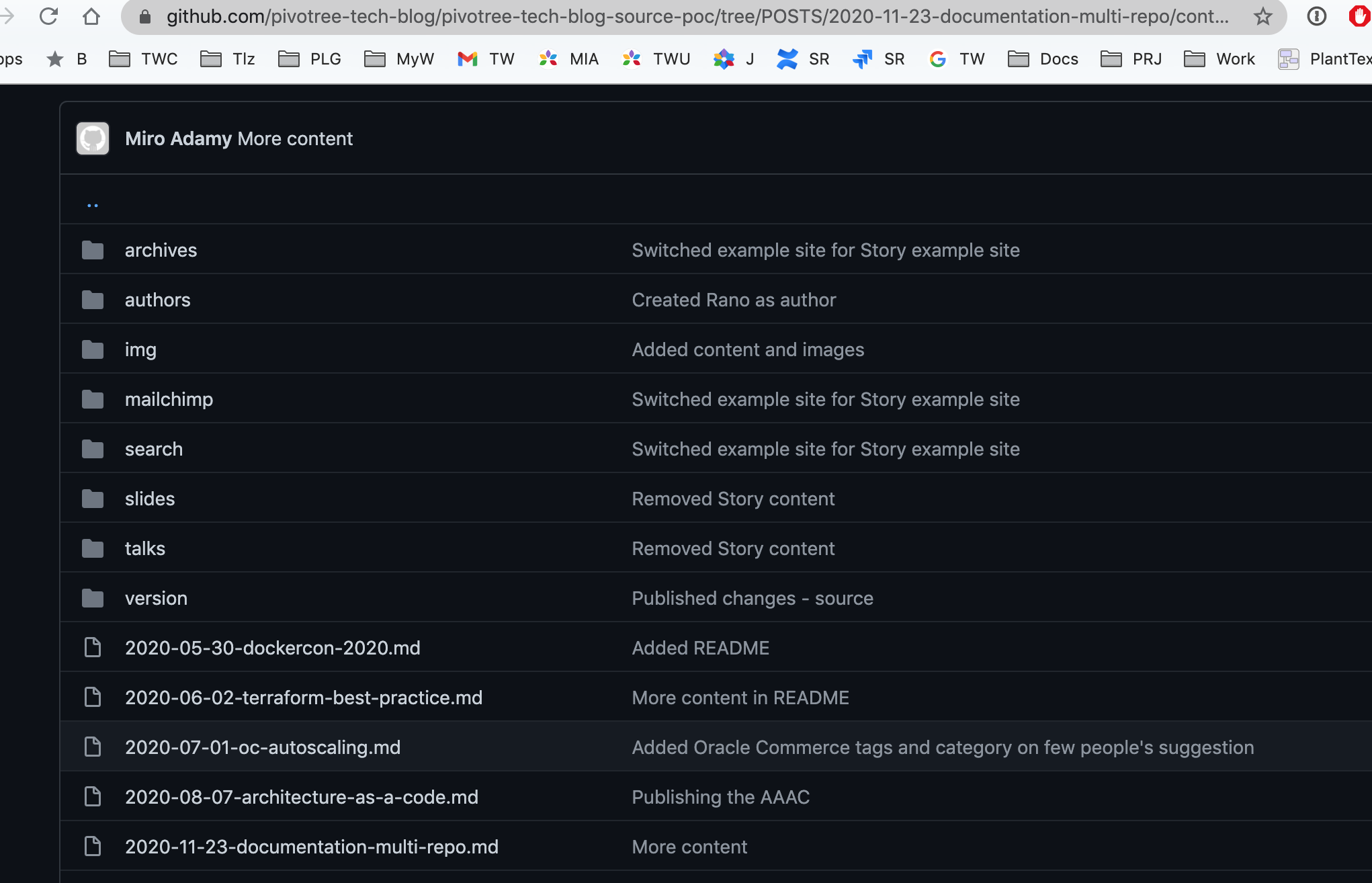

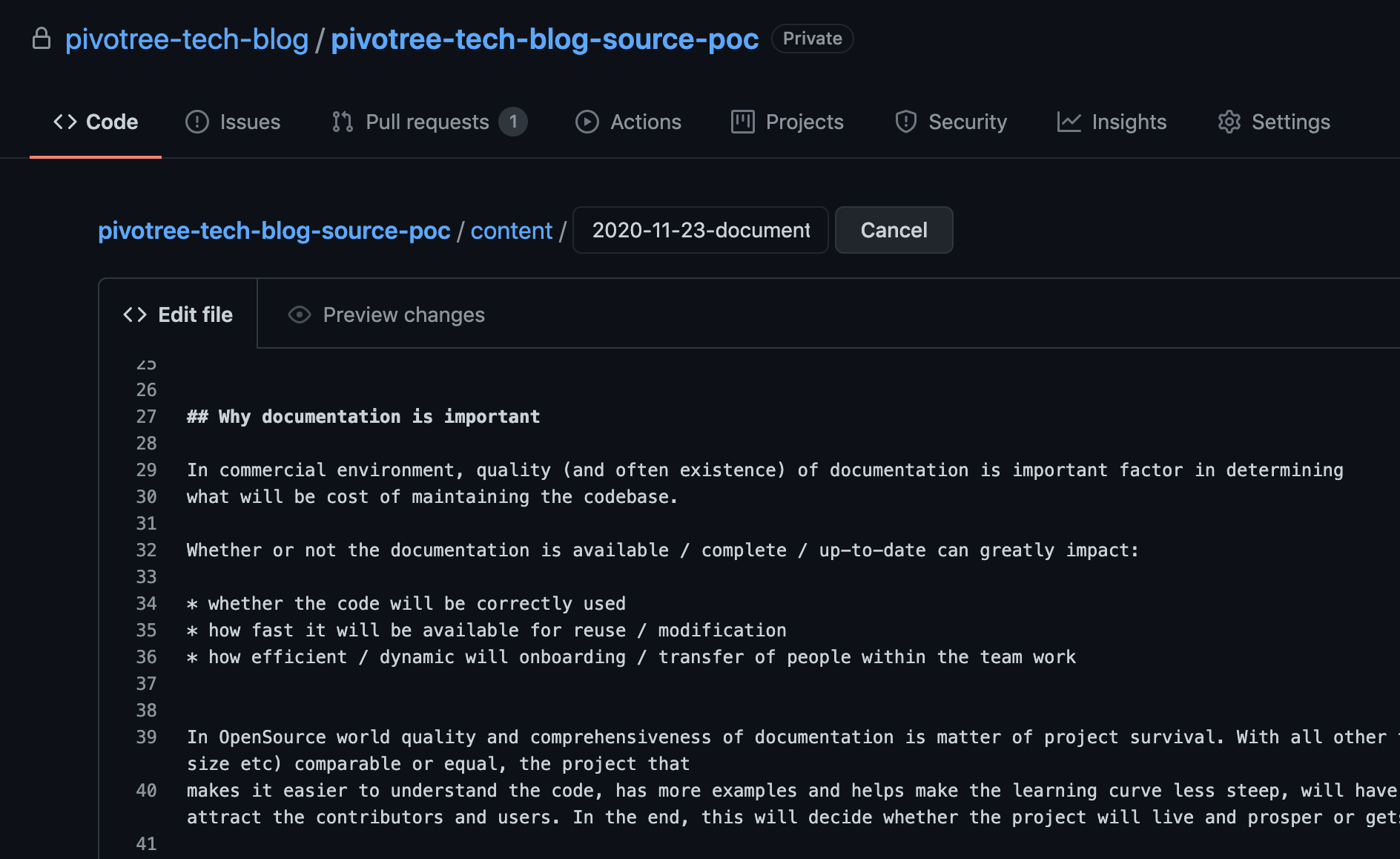

First get access to the repository on Github, Bitbucket or Gitlab - whatever your project uses. Then simply find the file in the repository and open it.

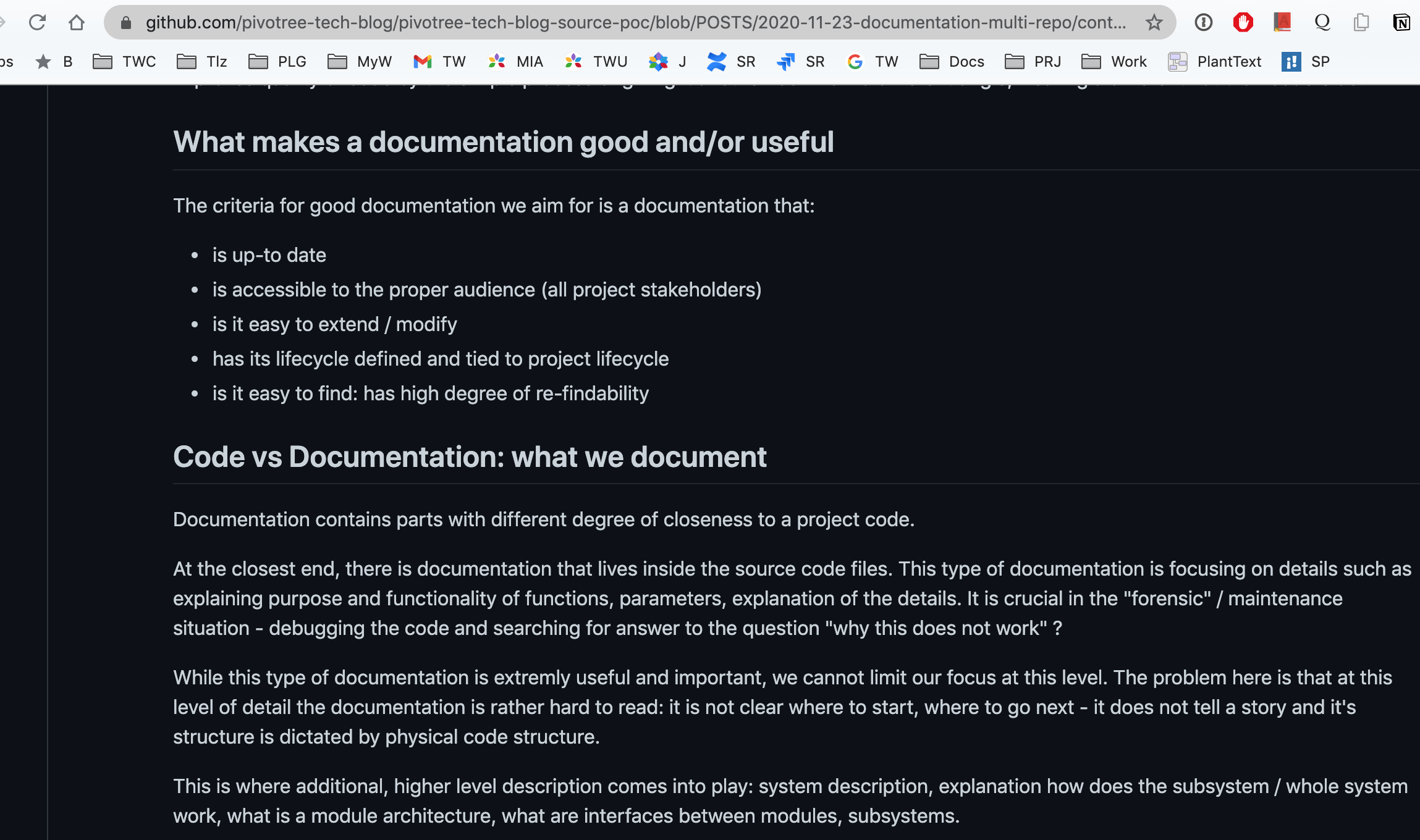

You will notice that it renders as a nice formatted web page (this is the preview mode).

In order to change the file, you need to switch to Edit mode.

The browser now offers you a “source” version of the file in Markdown.

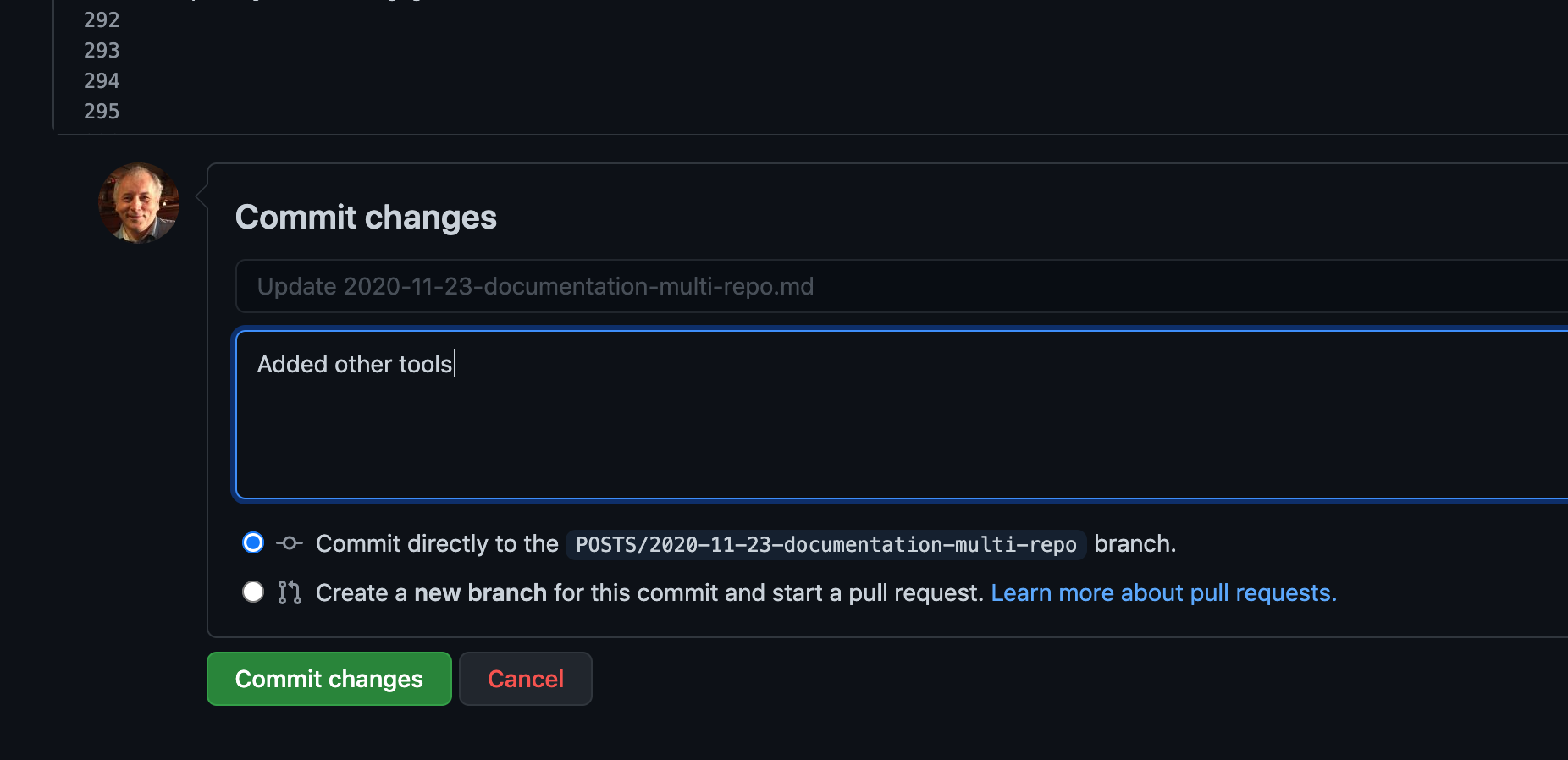

Make the changes you want and save the changes by making commit. There are two ways to save: either by simply adding the new version of the file to the repository history or by creating a pull request - a separate area where you change will be kept, allowing somebody to review it and merge it with the rest of the changes other developers may be doing.

If you are new to this, here are some pointers:

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/source-code-management

- https://bitbucket.org/blog/edit-your-code-in-the-cloud-with-bitbucket

- https://docs.github.com/en/free-pro-team@latest/github/collaborating-with-issues-and-pull-requests/about-pull-requests

- https://docs.gitlab.com/ee/topics/gitlab_flow.html

The main point here is that from a content creator experience point of view, this gives you very similar tools as Wiki without disadvantage of working on a separate system, away from development workflow. Your documentation will become an integral part of the development flow and will not drift or diverge because the documentation writers are separated from the codebase and unaware of the latest changes.

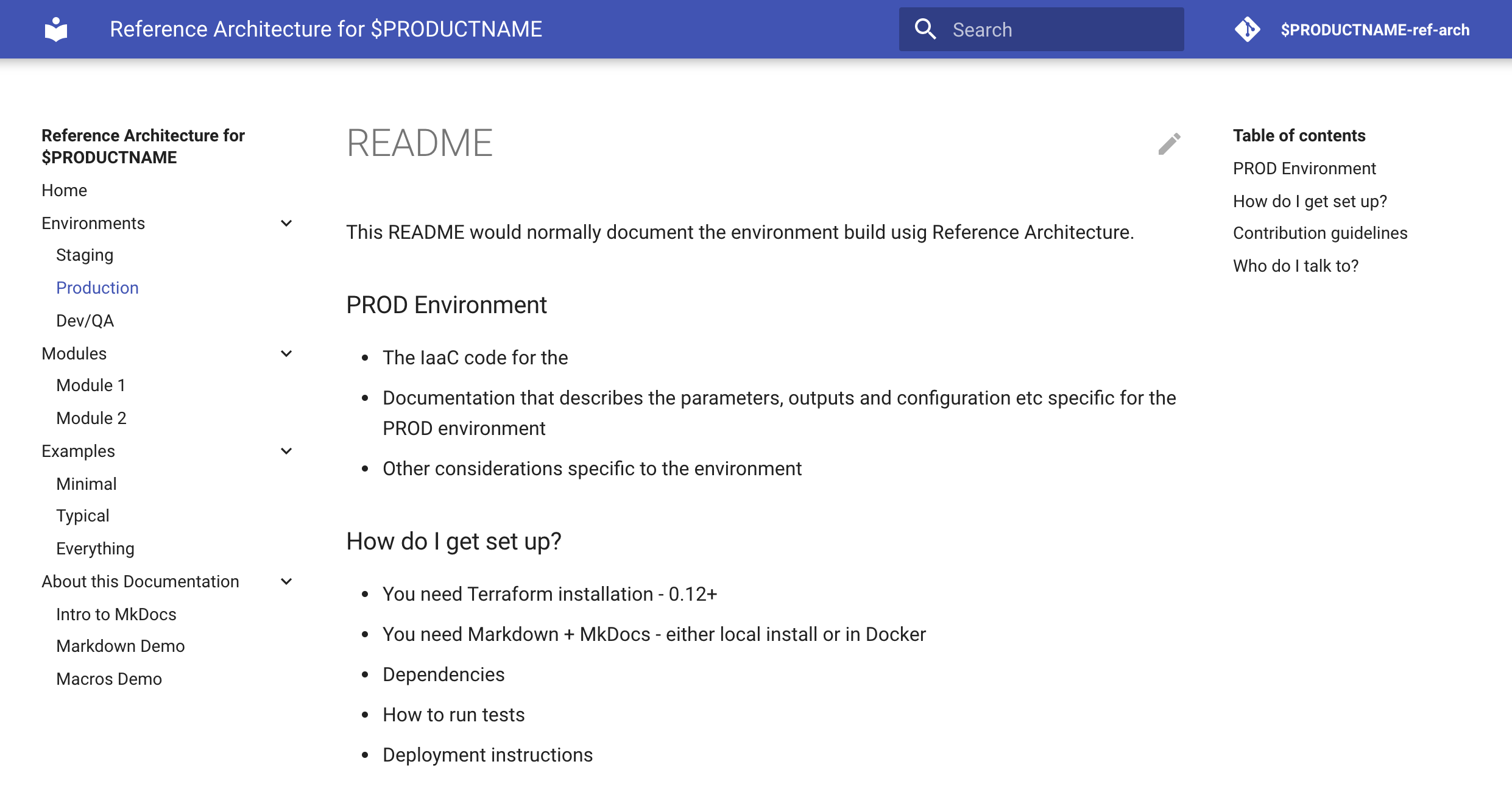

Organization of the Doc and Code: MkDocs

The above flows - Web based or developer oriented - were addressing the process of working with a single file. Most project will have many documentation files. They are useful on their own, but there is a simple way to define a navigational menu and turn them to dynamically generated web site with left side navigation bar and right-side file structure preview. This is what MkDocs does for us.

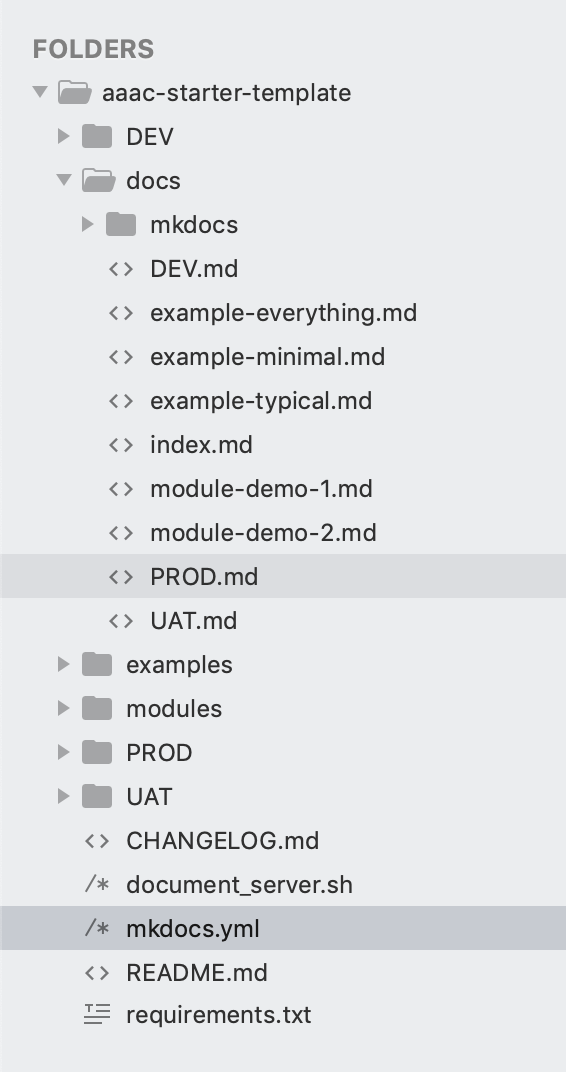

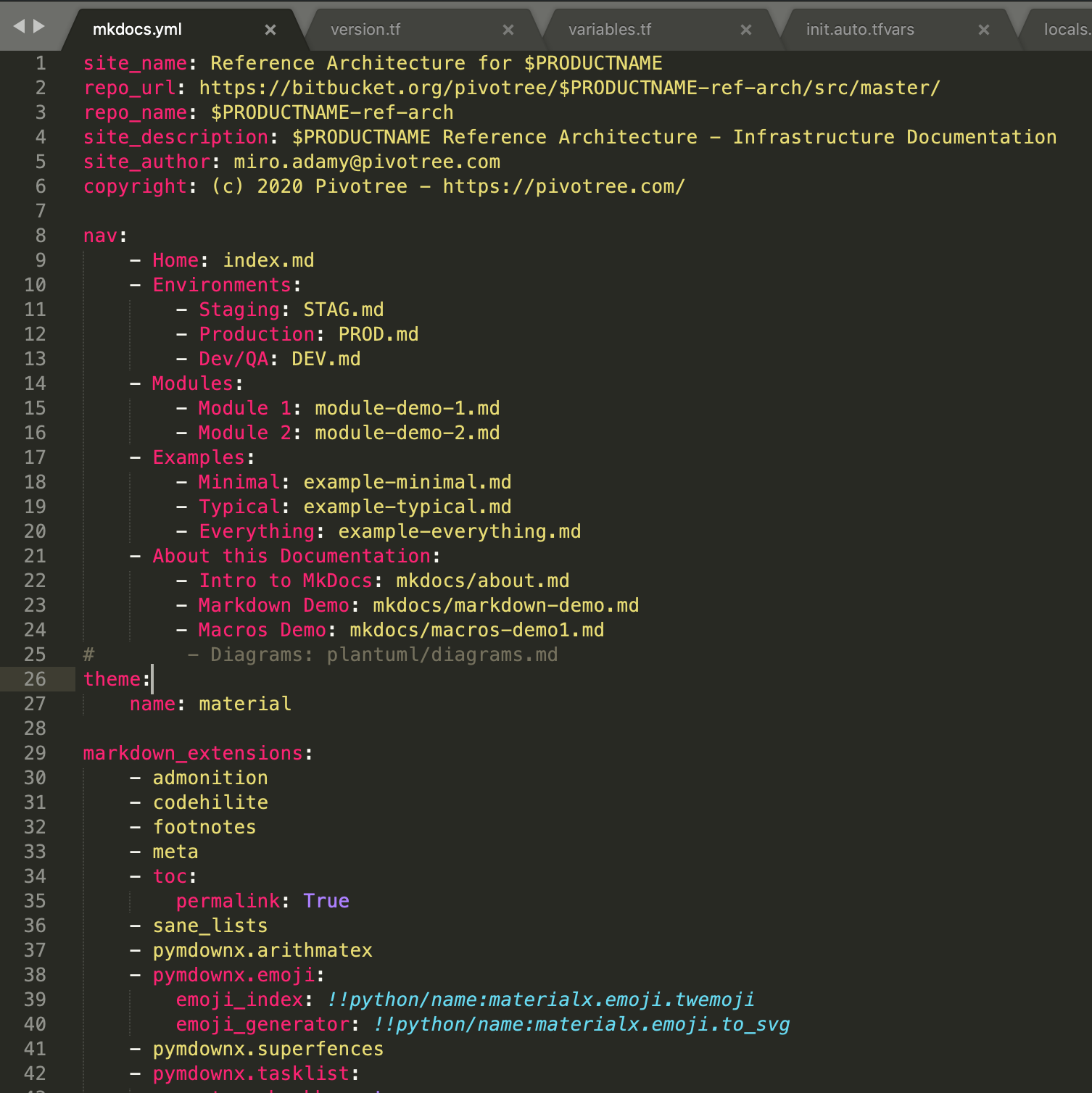

To make repository work with MkDocs, two things are necessary:

- put the Markdown files under

./docsfolder - add file

mkdocs.ymlto the root of the project that defines configuration of the documentation

Here is an example of a config file

site_name: Reference Architecture for $PRODUCTNAME

repo_url: https://bitbucket.org/pivotree/$PRODUCTNAME-ref-arch/src/master/

repo_name: $PRODUCTNAME-ref-arch

site_description: $PRODUCTNAME Reference Architecture - Infrastructure Documentation

site_author: miro.adamy@pivotree.com

copyright: (c) 2020 Pivotree - https://pivotree.com/

nav:

- Home: index.md

- Environments:

- Staging: STAG.md

- Production: PROD.md

- Dev/QA: DEV.md

- Modules:

- Module 1: module-demo-1.md

- Module 2: module-demo-2.md

- Examples:

- Minimal: example-minimal.md

- Typical: example-typical.md

- Everything: example-everything.md

- About this Documentation:

- Intro to MkDocs: mkdocs/about.md

- Markdown Demo: mkdocs/markdown-demo.md

- Macros Demo: mkdocs/macros-demo1.md

# - Diagrams: plantuml/diagrams.md

theme:

name: material

markdown_extensions:

- admonition

- codehilite

- footnotes

- meta

- toc:

permalink: True

- sane_lists

- pymdownx.arithmatex

- pymdownx.emoji:

emoji_index: !!python/name:materialx.emoji.twemoji

emoji_generator: !!python/name:materialx.emoji.to_svg

- pymdownx.superfences

- pymdownx.tasklist:

custom_checkbox: true

- pymdownx.tabbed

- pymdownx.tilde

- pymdownx.magiclink

- pymdownx.details

plugins:

- search

- macros:

include_dir: .

extra:

price: 12.50

company:

name: Pivotree

address: March 450

website: https://pivotree.com/

It contains 5 parts:

- header - name of the site

- navigational structure - which files create site and how

- theme

- markdown extensions

- plugins (note the include_dir directive)

- extra data (can be used in parameters)

Here is the source code organization:

Navigation: SRC => Rendered

The generated site takes the navigation part of mkdocs.yml:

and renders a dynamic menu out of it.

The whole layout of the site is defined by the navigation and the used theme. It is material theme for MkDocs that works in the background and renders the 3-column view with navigation on the left, content in the middle and structure of currently displayed document in the right column

Documentation Generation and Hosting

The process of transformation of the Markdown files to a website can be fully automated using CI/CD pipelines in each of the major hosting sites. The best support (IMHO) has Gitlab where this is an OOTB feature:

This is .gitlab-ci.yml that generates HTML sites accessible as Gitlab Pages attached to the repository. The great advantage of Gitlab is support for private Gitlab pages for private repositories, which simplify setup for authentication / authorization.

image: python:3.8-buster

before_script:

- pip install mkdocs 'mkdocs-minify-plugin>=0.2'

- pip install 'mkdocs-git-revision-date-localized-plugin>=0.4' 'mkdocs-awesome-pages-plugin>=2.2.1' 'mkdocs-macros-plugin'

# Add your custom theme if not inside a theme_dir

# (https://github.com/mkdocs/mkdocs/wiki/MkDocs-Themes)

# - pip install mkdocs-material

pages:

script:

- mkdocs build

- mv site public

artifacts:

paths:

- public

only:

- master

Similar setup works for Github by generating the website into a second, dedicated “published” Github pages repository. Unlike in the Gitlab case, all Github pages are public. For more information, refer to this

Another option is dedicated hosting site for MkDocs documentatio ReadTheDocs which also supports Sphinx and RestructuredText

And of course, there is always an option to use mkdocs build and copy the generated static site from ./public site to the hosting provider - e.g. an S3 bucket.

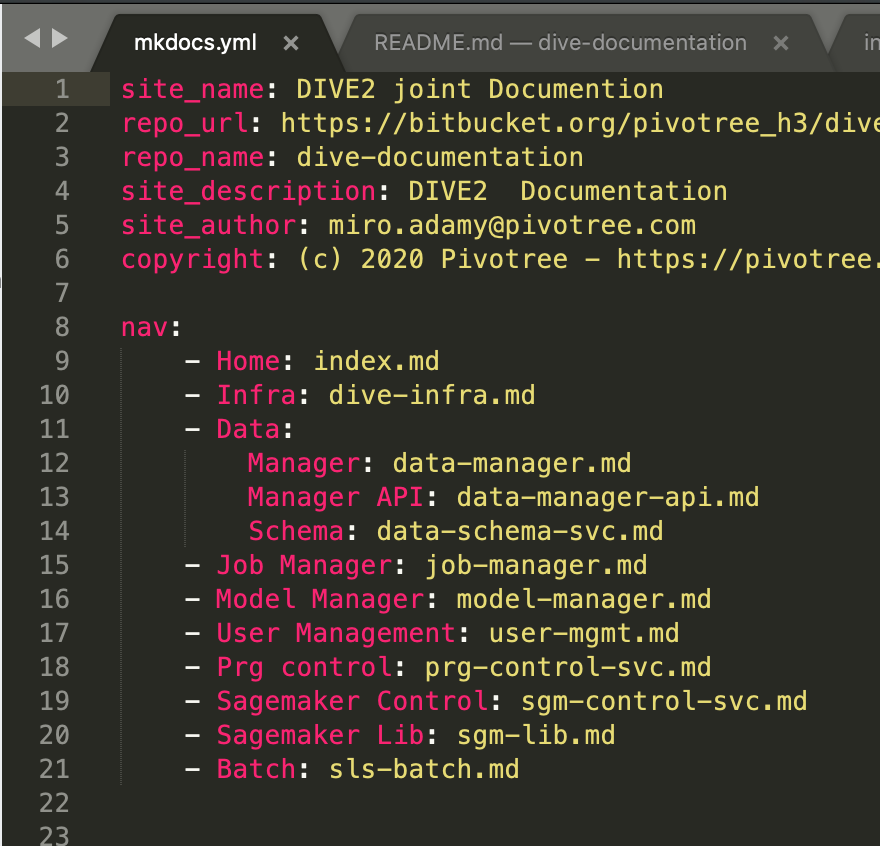

Single vs Multi-repository projects

In cloud native projects, it is very rare nowadays that all project code is stored in a single repository. With microservices, serverless, infrastructure as a code, GitOps etc we usually end up with quite a few different repositories. We can use the techniques above for documenting everything related to one repository - e.g. one microservice - but when it comes to documentation involving multiple components, we have a similar issue as with source code file vs documentation files: we have to put this doc files outside of the component repositories.

Each of the repositories internally uses it’s MkDocs structure and has its own mkdocs.yml file. For the documentation that does not belong to any particular component, we create another MkDocs repository that plays three roles:

- holds all documentation for all inter-modular parts

- holds main navigational tree and links to submodule specific navigation

- checks out all component modules as git submodules

As a proof of concept, we use this technique for documentation of the DIVE2 machine learning platform.

Here is the “top level” repository:

➜ tree -L 2

.

└── dive-documentation

├── CHANGELOG.md

├── README.md

├── dive-data-manager

├── dive-data-manager-api

├── dive-data-schema-svc

├── dive-infra

├── dive-job-manager

├── dive-model-manager

├── dive-prg-control-svc

├── dive-sgm-control-svc

├── dive-sgm-lib

├── dive-sgm-svc-template

├── dive-sls-batch

├── dive-user-mgmt

├── docs

├── document_server.sh

├── local-links.md

├── mkdocs.yml

├── pvt-python-commons

├── pvt-python-rest

├── pvt-sgm-color-norm-svc

└── tr-sgm-duplicates-svc

18 directories, 5 files

and here is the subset of the mkdocs.yml file:

site_name: DIVE2 joint Documentation

repo_url: https://bitbucket.org/pivotree_h3/dive-documentation/src/master/

repo_name: dive-documentation

site_description: DIVE2 Documentation

site_author: miro.adamy@pivotree.com

copyright: (c) 2020 Pivotree - https://pivotree.com/

nav:

- Home: index.md

- Infra: dive-infra.md

- Data:

Manager: data-manager.md

Manager API: data-manager-api.md

Schema: data-schema-svc.md

- Job Manager: job-manager.md

- Model Manager: model-manager.md

- User Management: user-mgmt.md

- Prg control: prg-control-svc.md

- Sagemaker:

- Sagemaker Control: sgm-control-svc.md

- Sagemaker Lib: sgm-lib.md

- Service Template: sgm-svc-template.md

- Duplicates Svc: tr-sgm-duplicates-svc.md

- Color Normalization: pvt-sgm-color-norm-svc.md

- Batch: sls-batch.md

- Libs:

pvt-python-commons: pvt-python-commons.md

pvt-python-rest: pvt-python-rest.md

theme:

name: material

markdown_extensions:

... DELETED ...

plugins:

- search

- macros:

include_dir: .

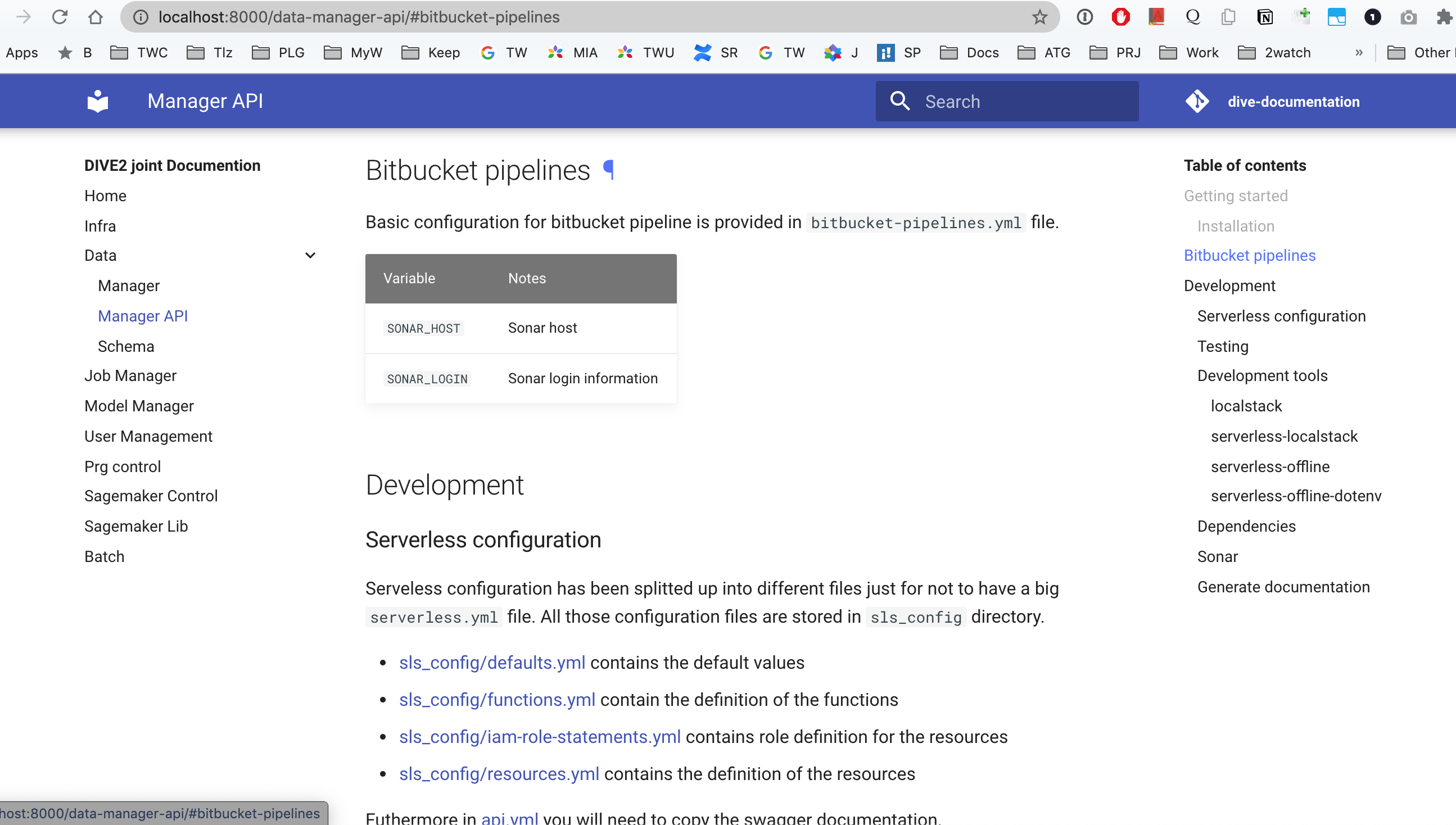

The rendered website reaches into the submodules and displays information from services in one consistent unit, combined with additional information about architecture, module relations ect. All this without duplication or requirements for the service team to work outside of their area of focus.

The mechanics is quite simple. The main menu - nav structure - refers to the files representing the submodule entry points. These files are located in the docs directory of the “roof” repository.

➜ dive-documentation git:(master) tree docs

docs

├── data-manager-api.md

├── data-manager.md

├── data-schema-svc.md

├── dive-infra.md

├── index.md

├── job-manager.md

├── model-manager.md

├── prg-control-svc.md

├── pvt-python-commons.md

├── pvt-python-rest.md

├── pvt-sgm-color-norm-svc.md

├── sgm-control-svc.md

├── sgm-lib.md

├── sgm-svc-template.md

├── sls-batch.md

├── tr-sgm-duplicates-svc.md

└── user-mgmt.md

0 directories, 17 files

How are these files hierarchically arranged is decided in the nav part of the YML file:

Each of this file contains one or more include directives, which are operating from the top directory of the repository and have therefore access to any submodule markdown files:

➜ dive-documentation git:(master) cat docs/model-manager.md

{% include 'dive-model-manager/README.md' %}

If the structure of the submodule is more complex, the “module file” can contain more directives or links.

When all this is put together, we get a combined, unified view of the system documentation with all submodules included. It is fully in the hands of the services team what the service documentation looks like and it is fully in the hands of the documentation repository maintainer which of those will be published and where in the navigation tree.

Other tools:

During last couple of months, we have looked at and used several other systems related to documentation generation

- Antora - Asciidoc based, multi-repo system

- Hugo - Go template based Markdown generator

- Jekyll / Hyde - another generator, Ruby based

but this post is getting way too long, so I will get back to some of them in the future.

There is certainly no shortage of available generators and solution - check the dedicated site. My colleague wrote a continuation with detailed case study on one of them in this blogpost

Author Miro Adamy

LastMod 2020-11-23

License (c) 2006-2020 Miro Adamy